Dongqi Jiang*

Ulink College of Shanghai, Shanghai 201615, China

*Corresponding email: 13758298841@163.com

https://doi.org/ 10.71052/hkfb2025/CTXA0192

Abstract

Land transfer policies are fundamental to China’s real estate market, yet research on rural collective land remains limited due to its incomplete marketization. Existing studies primarily focus on major first-tier cities (Shanghai etc.), leaving gaps in understanding emerging cities like Hangzhou. This study examines how migration-driven land supply affects the real estate market, urbanization, and land-use diversification through policy text analysis and case studies. Findings reveal that land transfer policies optimize market structures, enhance land-use efficiency, and promote social welfare while intensifying market competition. Sustainable development policies further facilitate a multi-stakeholder win-win outcome. The study concludes with policy recommendations and future research directions, considering Hangzhou’s comparative advantages while acknowledging data limitations.

Keywords

Land transfer policies, Real estate market, Urbanization, Rural land, Hangzhou

Introduction

Land has long been the cornerstone of Chinese civilization, shaping its social, economic, and political landscape. The advent of socialism in modern China brought about transformative land reforms in the 20th century. In the late 1950s, the collectivization of land through the Peoples Commune system eliminated individual land contracts, lowering productivity and land utilization. The 1978 introduction of the Household Responsibility System allocated land use rights to households while retaining collective ownership, establishing the separation of three rights—ownership, contracting, and management—thereby laying the legal foundation for land transfer policy.

Subsequently, in the end of the 20th century, with the progress of industrialization and urbanization in China, rural migration to cities resulted in a significant amount of underutilized rural land [1]. To improve agricultural productivity and accelerate the modernization of the rural economy, the Chinese government issued the Land transfer policy, which refers to the legal framework under which rural collective economic organizations or farmers transfer their contracted land-use rights to other operators (such as individuals or enterprises) for agricultural production or other uses, aimed at improving land-use efficiency and promoting rural economic development.

This essay selects Hangzhou, which presents a unique opportunity for case study, and analyzes the land transfer policies’ impact on Hangzhou’s real estate market [2]. This study will further explain urban-rural integration, stabilizing housing prices, and mitigating negative externalities, addressing three pivotal queries:

(1) How does the increase in land supply affect the supply, demand, and price of real estate?

(2) How does land transfer promote urbanization and housing demand?

(3) What is the impact of rural land conversion on urban real estate market structure?After introducing the key questions, the remainder of this essay will be structured as follows: The paper will review previous research on land transfer policies, applying property rights theory and institutional economics to analyze changes in property rights, institutional arrangements, and stakeholder dynamics. Case studies will be used to link theoretical frameworks to these core research questions. Additionally, limitations will be addressed to strengthen logical coherence. Finally, the paper will conclude with policy recommendations and future research directions.

Literature review

Recent developments in land transfer policies

Since China’s reform and opening, with the advance liberalization of land-related policies, the gradual maturity of land transfer policy has increased its impact on the real estate market. It can be known from the latest academic research in recent years that the impact of land transfer policy on the real estate market can be analyzed in the following aspects:

(1) Migration and housing demand

The land transfer policy has significantly promoted rural-to-urban migration because the relaxation of land policies has reduced restrictions on rural labor mobility, facilitating the migration of rural populations to urban areas. For instance, the rural area population in China decreased from 714.96 million in 2007 to 509.92 million in 2020, indicating a decrease of 200.54 million, leading to an increase in the urban population scale, which directly raises the demand for housing. In addition, this increased demand, in the context of inelastic housing supply in the short term, tends to drive up housing prices in urban areas, especially in China’s major cities.

(2) Urbanization and Economic Development

Urbanization is rapidly increasing, with the 2020 census showing 901.99 million people living in urban areas, a 14.21% rise from 2010. This shift significantly impacts on the real estate market. Urbanization boosts productivity and economic growth, increasing housing demand. Higher urban wages enhance the consumption and drive service sector and infrastructure expansion, fostering innovation and entrepreneurship. This leads to a positive feedback loop where increased consumer confidence and housing supply meet demand, benefiting both the economy and real estate market.

(3) Utilization and diversity

Urbanization boosts land use efficiency and diversification. Land transfer policies convert unused rural land to urban uses, simplifying land acquisition and encouraging market reforms. This helps governments and developers access land easily, speeding up urbanization. By focusing on urban growth, they reduce fragmentation, enhance resource efficiency, and cut infrastructure costs. This concentrated development saves resources, improves services, and makes urban areas more accessible, stimulating economic activity. The policy also diversifies land use, supporting industrial, commercial, and residential growth, affecting the real estate market by potentially increasing housing demand and causing price fluctuations.

Policy evolution

The evolution of China’s land transfer policies is divided into three stages. The first began in 1978 with “Reform and Opening up,” laying the groundwork for future land policies. The second stage started in 1988 with the Land Administration Law, allowing paid land use rights transfers and legalizing land circulation. The third stage, from 2003 onwards, saw improvements in land contracting and use rights laws, advancing land circulation’s marketization and standardization [7].

(1) From 1978 to 1987

The early land transfer policy was based on the rural land contract responsibility system. The 1982 Constitution separated land use rights from ownership but did not yet allow transfers. The Household Responsibility System gave farmers more land rights, paving the way for future transfers. The 1986 Land Management Law improved land management. In 1987, Shenzhen piloted paid land use rights transfers, marking a key reform step. Later that year, reforms were evaluated in several cities, and Shenzhen held the first state-owned land auction, advancing land use reform.

(2) From 1988 to 2003

Following pilot programs, the 1988 amendment to China’s Land Administration Law, influenced by the State Council, introduced Clause 4. This clause removed restrictions on land transfers, permitting legal rights transfers for state and collective lands, although specifics were to be determined later. This change sets the stage for future policies [8]. In 1993, the 14th CPC Central Committee allowed legal land rights transfers without mentioning compensation. By 1998, the 15th CPC Central Committee legalized voluntary, compensated transfers of farmers’ land use rights.

(3) Maturation Period (2003-Present): Comprehensive Development and Reform

In the 21st century, China’s land transfer policies were crucial for rural revitalization. The 2003 Rural Land Contracting Law allowed land transfers through subletting and leasing, with 17.8% of land transferred by 2011. The 2007 Property Law recognized farmers’ rights to use and transfer land for profit. The 2009 law improved dispute resolution. The 2013 “three-rights separation” let contracting and operating rights coexist. The 2016 policy supported collective ownership and liberalized operating rights, aiding resource allocation and moderate-scale farming. By 2017, 37% of contracted land was transferred, boosting rural development and agriculture modernization.

Methodology

Research methods and case collection

This study primarily employs textual analysis and case study methods for research. Historical legal provisions referenced span from 1982 to 2024, while data on Hangzhou is drawn from the years 2017 to 2023. Hangzhou is selected as the case study due to its strategic importance. As a newly designated first-tier city, it plays a crucial role in making up the research gap for emerging first-tier cities compared to old ones (Beijing, Shanghai etc.), while exemplifying the dynamics of land transfer policy implementation, with its high land transfer rate. Additionally, its innovative policy approaches and rapidly evolving real estate market—where average housing prices increased by 21.36% (27,851 yuan/square meter rose to 33,796 yuan/square meter) from December 2020 to December 2023—make it an ideal subject for analyzing the relationship between land transfer policies and real estate development.

Policy analysis

Based on the previous discussion of policy evolution, the legal provisions of the 1980s reflect a trend of gradually relaxing land control from a conservative stance to a more liberal approach in response to the unique historical context. Table 1 is a comparison and analysis of the 1982 Constitution and the 1986 Land Administration Law, presented in a chart format across four aspects: Main content, Legal framework & Restrictions, Linguistic differences, and the Impact on land transfer.

Table 1. Comparison and analysis.

| Legal Provisions | Main Content | Legal Framework & Restrictions | Linguistic Differences | Impact on Land Transfer |

| 1982 Constitution | Established socialist public ownership of land, with urban land belonging to the state and rural and suburban land belonging to collectives (Source: Article 10). Strictly prohibited the appropriation, buying, selling, renting, or transferring of land. | Separation of land ownership: urban land is owned by the state, and rural and suburban land by collectives. Strict prohibition of illegal transactions and land transfer, reflecting high government control over land. | The wording emphasizes that “no organization or individual may illegally sell, lease, or transfer land,” underscoring strict management of land. | Land transactions or transfers are strictly controlled, and no organization or individual may engage in illegal land transactions. Land transfer is limited to legally specified circumstances. In practice, this provision lacked operability. |

| 1986 Land Administration Law | Clarified the concept of land use rights, stipulating the procedures for land requisition, allocation, and transfer. Prohibited the transfer of ownership of collective land but allowed for the transfer of land use rights (Source: Article 2, Clause 2). Emphasized that the transfer of land use rights must follow legal procedures to prevent excessive marketization of land. | Land use rights transfer is regulated, especially for collective land use rights. Emphasized that “no organization or individual may illegally sell, lease, or transfer land,” maintaining strict government control over land use. | The wording stresses that “no organization or individual cannot be transferred, but the transfer is permitted for land use rights, confined to transactions within collective economic organizations. The law stresses strict procedures for land transfer to prevent speculative practices and social instability. Overall, the law marks a gradual relaxation of control. | Ownership of collective land cannot be transferred, but the transfer is permitted for land use rights, confined to transactions within collective economic organizations. The law stresses strict procedures for land transfer to prevent speculative practices and social instability. Overall, the law marks a gradual relaxation of control. |

Because China was transitioning from a command economy to a more market-driven economy at that time, there were substantial concerns about social stability and economic equality. The following punishments aimed to safeguard against speculative practices and the potential inequality that could arise if land became a privatized commodity too quickly. In Chapter 6, “Legal Responsibilities,” of the Land Administration Law, the penalties and consequences for illegal transactions or land occupation are reaffirmed. The examples are given below in Table 2.

Table 2. The penalties and consequences.

| Clause | Applicable Party | Violation | Penalty Measures |

| Article 43 | State-owned and urban collective units | Unauthorized or deceptive land occupation | Return land, demolish or confiscate buildings and facilities within a time limit, fine, administrative sanction for responsible personnel |

| Article 44 | Township or village enterprises | Unauthorized or deceptive land occupation | Return land, demolish or confiscate buildings and facilities within a time limit, possible fine |

| Article 45 | Rural residents | Unauthorized or deceptive residential construction on land | Return land, demolish or confiscate house within a time limit |

| Article 46 | Urban non-agricultural residents, state employees | Unauthorized or deceptive residential construction on land | Return land, demolish or confiscate house within a time limit, administrative sanction for state employees |

The use of terms like “confiscated” and “administrative sanctions” in historical policies reflects China’s cautious approach to maintaining public land ownership [9]. The Land Administration Law was significantly amended in 1988, allowing legal transfers of both state-owned and collective land use rights, marking a shift from strict control to market-oriented land policy. This change paved the way for land market operations.

The Seventh Five-Year Plan (1985-1990) emphasized rural economic reforms, including land contracting, which laid the groundwork for marketizing land transfers. The 1991 Land Management Law Implementation Regulations further clarified land use, management, and transfer regulations. Local governments were responsible for registering and issuing certificates for both state-owned and collective lands, providing a legal basis for land transfers [10].

However, as land management regulations relaxed, rural land markets became chaotic, with disputes often arising over land contract management rights. The 1998 revision of the Land Management Regulations added Article 6, requiring applicants to hold approved documents and submit land change registration applications for land use changes. Article 7 specified regulations for recovering land use rights when contracts expire, or extensions are denied.

In the 21st century, the 2002 Rural Land Contract Law was enacted to advance land use rights circulation. It established farmers’ rights to contract and manage land, ensuring long-term stability with 30-year contract periods. The law allowed for the lawful transfer of contractual land operating rights, shifting from control to encouragement of land circulation while protecting farmers’ rights. This law marked a significant development in rural land transfer policies, promoting the marketization of land use rights transfer.

From 1982 to 2004, rural labor migration in China fluctuated significantly, peaking at eight million in 1993 before dropping to 2.23 million in 1996. After 2001, migration rates increased again, reaching over one hundred million migrants by 2004, accounting for 20.6% of the rural labor force. This migration led to land idleness, prompting new laws to address the issue.

Land expropriation disputes were common due to unclear guidelines for local governments, leading to conflicts overcompensation. For instance, a court case involving Zhan Xinglong sought compensation for land, but was dismissed as the contract was deemed valid [11].

To resolve these issues, new documents were introduced, focusing on the “separation of three rights” in rural land: ownership, contract, and management rights. This has led to a more stable land transfer system, with significant policies from 2008 to 2021 supporting this development.

According to Table 6, this decision primarily outlines the process of establishing a unified urban and rural construction land market, alongside standardized regulations, and improvements for the transfer of land use rights through an open and unified tangible land market. This ensures that legally acquired rural collective management construction land enjoys equal rights and interests with state-owned land, provided it meets planning requirements [12].

The next table demonstrates the contents of the “Opinions on Promoting Stable Agricultural Development, Sustainable Income Growth for Farmers, and Urban-Rural Integration” (2009). This policy promotes land rights confirmation, regulates the transfer of collective construction land, and supports agricultural land facility, gradually establishing a unified urban-rural construction land market. Its impacts include boosting rural land market activity, protecting farmers’ land rights, supporting collective economic growth, optimizing land resource use, and facilitating coordinated urban-rural development.

Table 3. The impact and categories of these Opinions.

| Category | Powers | Ownership | Characteristics | Policy Content | Policy Impact |

| Basic Farmland Protection | Restriction on non-agricultural use, ensures centralized farmland management | State and rural collectives | Consolidated, high-standard grain production | Consolidate farmland. | Preserves arable land resources, ensures food security, and optimizes land utilization. |

| Agricultural Land Rights Confirmation and Transfer | Registration of rights, transfer of contracted management rights | Rural collectives | Defined ownership, facilitates land transfer | Transfer land, confirm rights. Confirmation. | Clarifies land ownership, protects farmers’ land rights, stimulates rural land markets, and supports modern agriculture. |

| Collective Construction Land Transfer | Rights confirmation, transfer of usage rights | Rural collectives | Standardized transfer promotes marketization | Confirm collective land rights. | Enhances transfer efficiency, protects collective and farmer rights, promotes integration of urban and rural land resources. |

| Rural Residential Land | Separate quotas for homesteads, supports housing for farmers | Rural collectives | Separate allocation for rural residential construction | Provide homestead quota. | Meets rural housing needs, prevents homestead shrinkage, improves living conditions, supports urban-rural balance. |

| Facility Agricultural Land | Excluded from agricultural land conversion, supports facility agriculture | Rural collectives | Reserved for agricultural facilities, does not count toward construction land quota | Facility land is not in quota. | Flexible land policies promote agricultural facilities development, modernize agriculture, and increase rural land use efficiency. |

The first policy speeds up land surveys to define ownership and use rights for rural land, including homesteads, to quickly register and certify them. The second policy creates a unified land market for urban and rural construction, allowing rural collective land to be transferred, leased, or invested on par with state-owned land, provided it follows planning and usage regulations. These policies aim to create a fairer land market, boosting rural land value and fostering integrated urban-rural development [13].

Following the registration of rural land management rights and land ownership and use rights, the Fifth Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in 2015 emphasized improving the separation of land ownership, contract, and management rights. In 2016, guidelines were issued to detail this “three rights separation,” enhancing clarity and management of rural land rights [14].

The evolution of China’s rural land property rights transfer system has seen notable advancements due to policy liberalization, simplified transaction procedures, and rights clarification. By 2018, 21 provinces had introduced guidelines for rural property rights transfer markets, with 1,239 counties and 18,731 townships establishing service centers for transferring land operational rights. This development has led to a framework that suits rural conditions and the nature of land rights transfer (Han, 2018).

The Rural Land Contract Law of the People’s Republic of China, initially from 2002, has been revised twice. The 2009 amendment slightly altered terminology, replacing “expropriation” with “expropriation and requisition” in Articles 16 and 59. The 2018 amendment, however, was more substantial, extending contract terms to 30 years under Article 21 and renaming Section 4 to “Protection, Exchange, and Transfer of Land Contract Management Rights,” indicating a shift towards encouraging land transfers. The administrative measures that support this law, effective from 2021, highlight new developments stemming from the separation of ownership, contract, and management rights, further refining the management and transfer of rural land rights [15].

Background information on the Case

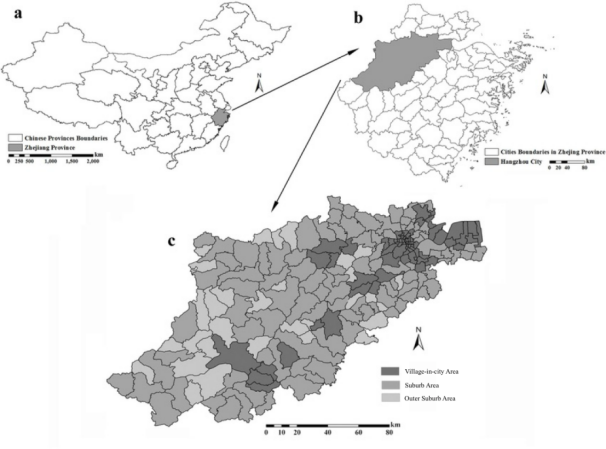

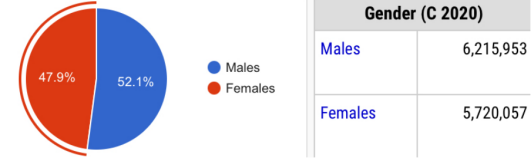

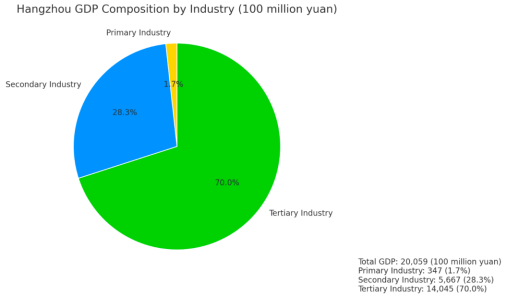

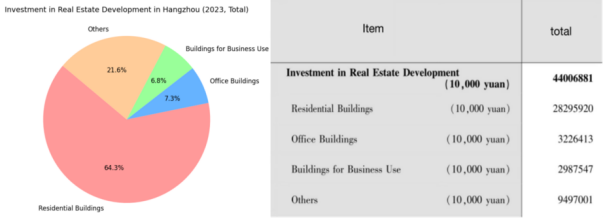

Hangzhou’s real estate market reflects the characteristics of developed coastal cities, giving it potential advantages in addressing contextual gaps in research and enhancing its research value. To present relevant data and information more concisely, the following graphs will illustrate Hangzhou’s administrative divisions, population distribution, economic development levels, and land resource utilization structure in relation to land transfer policies.

Figure 1. The distribution of land in Hangzhou.

(Source: China National Bureau of Statistics, 2024)

Figure 2. The gender distribution In Hangzhou.

(Source: China National Bureau of Statistics, 2023)

Figure 3. The economic development level in Hangzhou.

(Source: China National Bureau of Statistics, 2020)

Figure 4. The investment in real estate development, Hangzhou,2023.

(Source: Hangzhou Municipal Bureau of Statistics, 2023)

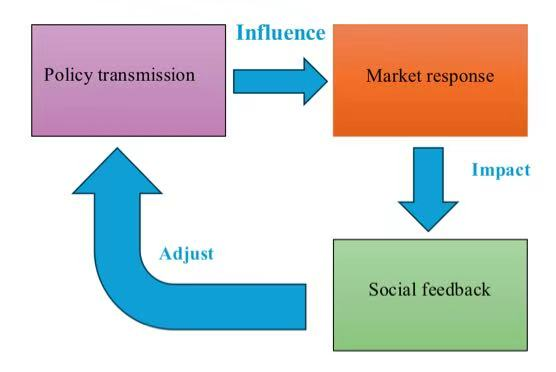

Based on the data and relevant policies provided in Chapter 3, this chapter employs a triple interaction analysis framework enriched with case studies. The effects of land transfer policy are reflected through three interconnected levels forming a logical feedback loop:

Figure 5. Triple interaction Framework.

Policy transmission level

The policy transmission level refers to how central land policies influence local real estate markets as they are implemented by local governments. This level primarily affects real estate markets through mechanisms such as direct price effects, supply structure effects, and regional restructuring effects:

(1) Direct price effect

Land transfer policies directly influence local land prices by affecting land supply which subsequently impacts housing prices. As discussed in Chapter Three, refinement of land transfer policies has allowed an increasing number of fragmented village collective lands to access land market through land transfer. With third amendment to Regulation for Land Administration Law in 2021 lowering entry barriers for collective rural land into market and optimizing land resource allocation; Yuhang District in Hangzhou recorded total land transfer area of 55,800 mu with transaction amounts reaching 9.5137 million yuan in 2023 marking historic high since administrative division adjustments in 2021; average land transfer price in Yuhang district decreased significantly alleviating cost burden on developers leading to reduction in construction costs for residential properties; average housing price in district fell from 25251 yuan per square meter in December 2023 to 23985 yuan per square meter in December 2024 reflecting overall reduction of 5.01% (CNBS,2023). Transmission of price may not simply lead to a linear relationship between land transfer policy and housing price because as land price is regulated to a low position through land policy, competition for winning ownership of land may ascend in opposite direction.

The above cases highlight complexity in how land transfer policies influence the real estate market through price mechanisms: beyond directly affecting average housing prices via cost transmission; these policies also drive price dynamics through competition and feedback among market participants leading to reform in supply structure of real estate market:

(2) Supply structure effect

As land transfers progress; rural collective agricultural land is gradually transitioned into urban areas converted into construction land; this transformation reflects diversification of land functions and further enhances land-use efficiency; taking Hangzhou as example; shift in purpose of agricultural and other collective land inevitably contributes to decline of primary industry while simultaneously driving rapid growth of secondary and tertiary industries; primary industry in Hangzhou accounts for only 1.7% of its GDP contribution significantly lower than other two sectors; this observation substantiates this transformation highlighting substantial advancements in productivity; since 2017; Huangpu Town in Hangzhou transformed agricultural land (mainly paddy fields) into construction land planning to add approximately 220 mu new construction land; creating modern landscape; town divided into three areas; west focuses on ecological development tourism forming rural cultural zone; center emphasizes urban development expansion modern agricultural park integrating city countryside; east follows government strategy to develop financial hub positioning it as long-term development zone; this case clearly demonstrates impact of land transfer policies in optimizing land functions improving land-use efficiency; accelerating urbanization generating positive externalities through restriction regional value (Hangzhou Planning and Natural Resources Bureau,2017):

(3) Regional restructuring effects

With advancement integrated urban-rural development; previously distinct dualistic structure has gradually transitioned into unified integrated composite structure; many village collectives have opted for mergers integration reconstructing value regions; In 2021; five village collectives in Qiantang District collaborated with local state-owned enterprise to develop and transfer reserved land under “Four Unified” principle emphasizing unified planning design construction acceptance service facilitation leaseback operations; this approach ensured systematic efficient land use; while land ownership remained with village committees; state-owned enterprise handled initial construction subsequent unified operations under 20-year lease agreement; planned high-end complex featuring commercial office hotel facilities benefits from its prime location near one of Hangzhou’s largest resettlement housing projects; upon completion project expected to generate additional annual income over 4 million yuan for village collectives; project will further enhance urban image along route fostering connections nearby semiconductor industry; this will drive high-quality industrial-urban integration area contributing overall value enhancement region; for example; project may provide offices for semiconductor industry create foundation hi-tech park (Hangzhou Municipal Peoples Government,2021):

Market response level

According to analysis of policy transmission level; we should also engage in in-depth discussion regarding market responses; Land transfer policies influence stakeholders in market through policy transmission mechanisms eliciting varied responses different market stakeholders; driven by objective utility maximization; stakeholders likely adjust strategies preferences accordingly; consequently overall market structure may undergo transformation accompanied by establishment price mechanism:

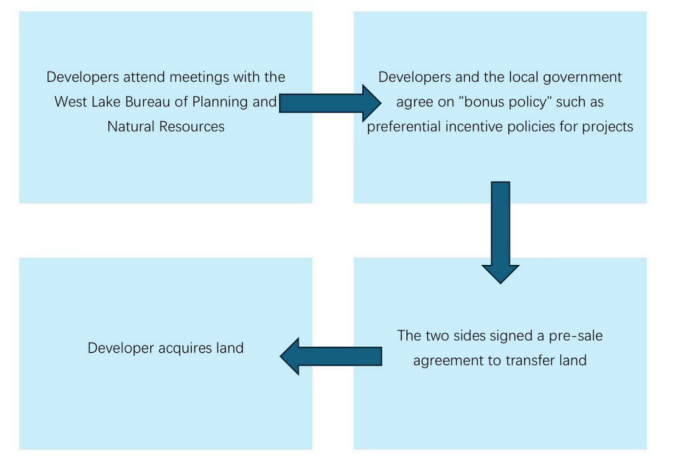

(1) Developers’ behavior response

As discussed in Section 4.1.1; increased supply in land market attracts more real estate developers participate in land auctions potentially driving land prices higher rather than lowering them; for instance; On December31;2024; Hangzhou final land auction year saw seven parcels of land collectively sold for 14.56 billion yuan with average premium rate of 30.1%; among these; Xining parcel in Bin Jiang District characterized by its prime location significant locational advantages achieved final premium rate of 59.78% (BCIA,2024); therefore; financial pressure for developers may be high; thus developers may change their land acquisition strategy; some well-funded large-scale developers facing capped land prices in prime locations where multiple bidders reach maximum price making difficult secure land; as a result; some developers opt assist government with remising or enter pre-sale agreements acquire land more conveniently; according Hangzhou Planning and Natural Resources Bureau (2024); flow chart (Figure below) illustrate situation:

Figure 6. Hangzhou XH0910-29 Land Parcel Project.

(Source: Hangzhou Planning and Natural Resource Bureau,2024)

The above case reflects developers’ responses to land policies and land acquisition strategies driven by profit motives; additionally, high land premium rates resulting in an increase in average housing prices have compelled developers to adopt innovative product positioning strategies to attract homebuyers leveraging higher-quality housing remain competitive real estate market.

(2) Homebuyers’ demand change

With developers’ product innovations and changes in reginal value; homebuyers’ demand structure preferences have also evolved; In Hangzhou; developers marketing strategies in 2024 have shifted focusing on price prioritizing quality emphasizing premium finishes smart home systems comprehensive community amenities; for instance; VIP appointment systems introduced allow potential buyers preview select properties in advance; therefore; demand improved housing become dominant; many buyers relocate

Conclusion

This study examines the evolution of China’s land transfer policy and its impact on Hangzhou’s real estate market. It finds that since the introduction of the rural land contract responsibility system in 1978, the policy has progressively supported urbanization and housing market growth, with subsequent laws like the Rural Land Contract Law providing clearer legal frameworks. Hangzhou’s housing market has shown a complex response to these policies, with increased land supply helping to balance demand, stabilize prices, and encourage economic diversification. Additionally, the policies have spurred urbanization and rural development, providing farmers with stable income and greater urban engagement. The study recommends enhancing legal frameworks, increasing supervision to prevent illegal activities, and fostering urban-rural integration to optimize land resource allocation and infrastructure. It suggests that future research should focus on long-term effects, regional comparisons, and international perspectives to further understand the policy’s broader implications.

Acknowledgements

This work was not supported by any funds. The authors would like to show sincere thanks to those techniques who have contributed to this research.

References

[1] Zhang, Z. Q., Li, M. J., Li, W. J., Wei, Y. R., Shi, Y. L. (2023) A long way to go: impacts of urbanization on migrants’ livelihoods and rural ecology in less industrialized regions. Journal of Mountain Science, 20(12), 3450-3463.

[2] Zhu, W., Chen, J. (2022) The spatial analysis of digital economy and urban development: A case study in Hangzhou, China. Cities, 123, 103563.

[3] Tripathi, S. (2021) Do macroeconomic factors promote urbanization? Evidence from BRICS countries. Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science, 5(2), 397-426.

[4] Duca, J. V., Muehlhauser, J., Murphy, A. (2021) What drives house price cycles? International experience and policy issues. Journal of Economic Literature, 59(3), 773-864.

[5] Devlin, C., Coaffee, J. (2023) Planning and technological innovation: the governance challenges faced by English local authorities in adopting planning technologies. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 27(sup1), 149-163.

[6] Xu, G., Liu, J., Zhang, M. (2024) Land property rights, spatial form, and land performance: A framework of policy performance evaluation on collective-owned construction land and evidence from rural China. Land, 13(7), 956.

[7] Cattaneo, A., Adakai, A., Brown, D. L., Christiansen, L., Evans, D. K., Haakenstad, A., Weiss, D. J. (2022) Economic and social development along the urban–rural continuum: New opportunities to inform policy. World Development, 157, 105941.

[8] Li, C., Guo, G. (2022) The influence of large-scale agricultural land management on the modernization of agricultural product circulation: based on field investigation and empirical study. Sustainability, 14(21), 13967.

[9] Coggin, T. (2021) There is no right to property: clarifying the purpose of the property clause. Constitutional Court Review, 11(1), 1-37.

[10] Boateng, X., Ying, C., Tingting, P., Mak‐Mensah, E. (2024) A comprehensive review of the impact of farmland property rights stability on farmers’ land use and protection behaviors. Land Degradation & Development, 35(10), 3215-3225.

[11] Liu, P., Han, A., Ravenscroft, N. (2023) Improving farming practice through localized land tenure reform: a study of the “Three Rights Separation Reform” implemented in a Shanghai suburb, China. Geographies Tesseract-Danish Journal of Geography, 123(1), 11-24.

[12] Tan, L., Cui, Q., Chen, L., Wang, L. (2024) An Exploratory Study on Spatial Governance Toward Urban–Rural Integration: Theoretical Analysis with Case Demonstration. Land, 13(12), 2035.

[13] Haloumis, C., Ergotis, N. (2024) A historical analysis of the banking system and its impact on Greek economy. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology, 8(6), 1598-1617.

[14] Jiang, D., Yang, C. (2025) The impact of land transfer policies on the real estate market: A case study of Hangzhou. Journal of Urban Studies, 42(5), 689-712.

[15] Zhao, L. (2021) Land expropriation disputes in China: Legal challenges and policy responses. China Law and Government, 54(3), 223-245.